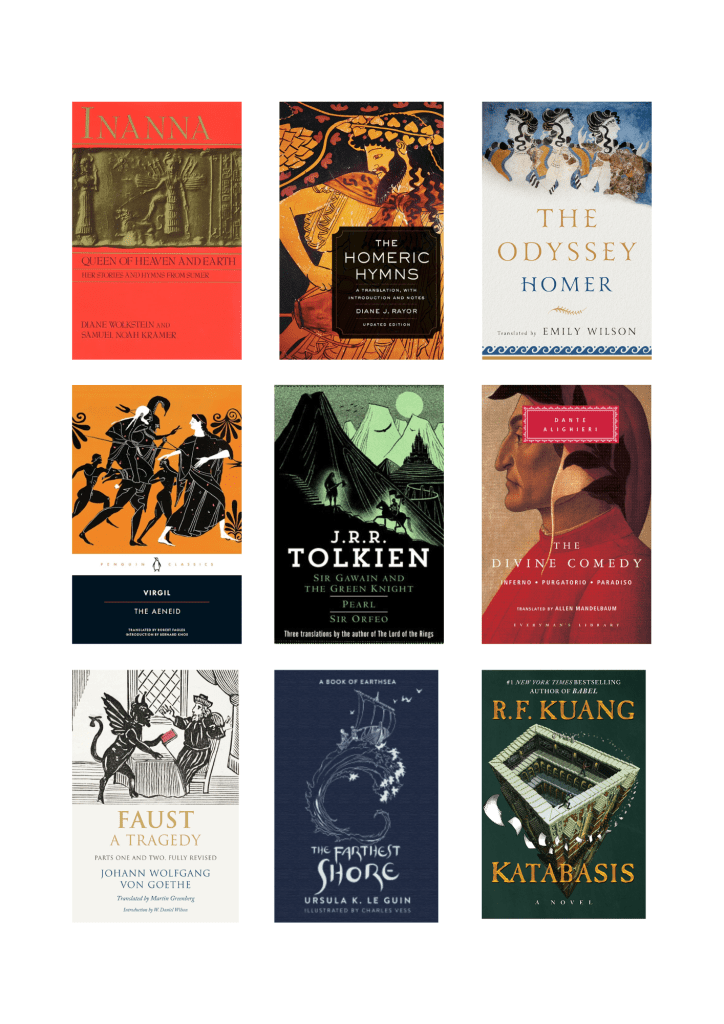

R.F Kuang’s highly anticipated novel, Katabasis, was published recently and it has brought on a wave of discourse around journeying into the underworld as a physical and metaphorical storytelling device! ‘Katabasis’ itself is a Greek term for the hero’s descent into the underworld usually referring to Hades.

We have covered many stories where our hero or protagonist journeys into the underworld as a symbol of death and resurrection (seasons) like Persephone in the Greek Hymn to Demeter, and the Sumerian stories of Inanna. We’ve also covered stories which feature voluntary travel to the underworld to fetch something, such as in Hiku and Kawelu and How the Moon was Made.

You can listen to our episode: Click here.

Television series featuring journeying and coming back from the underworld include Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Supernatural. Plays and musicals about Orpheus and Eurydice include Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown and Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice. There are a lot of video games featuring the Greek myths and Gods, but for simplicity we have Orpheus in Hades 1 and 2!

For fans of older texts, Tolkien has a wonderfully translated version of the Medieval text “Sir Orfeo” which is a Celtic retelling featuring Sir Orfeo recusing his wife from the fairy king.

The Greeks and Katabasis

Several of our Greek heroes physically journey into Hades and we’ll give you a brief overview of them:

- Theseus and Pirithous really wanted to choose new brides for themselves. They also thought they deserved daughters of Zeus, so while Theseus chose a very young Helen of Sparta, Pirithous decided to go after the already-married Persephone. The two men entered the underworld, but they did not make it very far before Persephone and Hades punished them by trapping them in chairs of forgetfulness with snakes coiled around them. Heracles eventually saved Theseus while he was on a journey to the underworld himself for his final labor of retrieving Cerberus, Hades’ multi-headed hell hound. However, Pirithous was not allowed to leave and remained stuck in his chair forever. For anyone wondering, Theseus returned to the mortal realm and found that Helen had been saved by her brothers, Castor and Pollux.

- Psyche, from the story of Psyche and Eros, was also tasked with traveling down to the underworld for a “labour” by Aphrodite. In this story, which we had covered when we discussed the Norwegian tale of East of the Sun, West of the Moon, Psyche married Eros, but he only came to her in the night, which made Psyche curious. One day, she secretly used an oil lamp to see his face while he was sleeping, but the hot oil dripped onto him, and he vanished. Distraught, she begged Aphrodite to let her see her husband, but Aphrodite refused until Psyche completed a list of impossible tasks, one of which was to journey to the underworld and retrieve a piece of beauty from Persephone. That was, of course, a very general summary of the tale, so I highly recommended reading Books 4–6 of The Golden Ass by Apuleius for more.

- In Books 9–12 of the Odyssey, Odysseus was advised by Circe to speak to the soul of the blind seer Teiresias- the only problem? The prophet was dead. So, Odysseus has to make a sacrifice and travel to the underworld, however, in order to speak to the shades, he has to offer them some of the blood. Amongst those he saw were Elpenor, his dead comrade who begged him to bury his body; his mother, who recounted the events in Ithaca; and a number of women who shared their names and stories, including Ariadne, who had helped Theseus with the Minotaur. He also saw Agamemnon, who told Odysseus of his murder at the hands of his wife, Clytemnestra, and toward the end he met Achilles and Heracles. His journey was to glean information as opposed to stealing the wife of the King of the undead or complete a trial

Jorge-Rivera Herrans’ EPIC: The Musical does a phenomenal job depicting Odyssey’s time in the underworld with the Underworld Saga.

Finally, we can turn to the man we are all here for! The myth of Orpheus and his journey into the underworld! One of the earliest mentions of Orpheus comes from a 6th century poet, Ibycus and later, the poets Pindar and Simonides. There are many sources we looked at, but the main texts we drew from are listed and linked down below. These also make a good starting point if you want a reading list curriculum focused on R.F Kuang’s Katabasis or if you are wondering what you should read before you read the book:

- Himerius’ Orations

- Pindar’s Pythian Odes

- Virgil’s Georgics and Aeneid

- Ovid’s Metamorphoses

- Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica

- The Orphic Argonautica

- Euripides mentions him briefly in many of his texts

- Jospeh Campbell’s Hero with a 1001 Faces

The Family Tree of Orpheus

This is the tale of Orpheus, son of the muse of epic poetry, Calliope. As is often the case with Greek heroes, his father was either a god or a mortal, and different versions refer to him as such. According to some like Pindar, his father was Apollo, but Apollonius and Diodorus Siculus named him as the son of the Thracian Olagrus (more commonly spelled Oeagrus).

Here we must pause, as the Greeks often did in their storytelling, to recount that Oeagrus potentially had two other notable sons, Linus and Marsyas.

According to Apollodorus, Linus had the unhappy misfortune of being a music tutor to Heracles, and after a particularly bad session in which Linus punished Heracles, the young hero attacked and killed the man. In another story regarding his death, Linus is killed by Apollo during a music contest.

This is interesting because the other (more sketchy) son of Oeagrus is Marsyas. Hygnius recounts in his Fabulae that “Marsyas, a shepherd, son of Oiagrus, one of the satyrs” found Athena’s discarded flute which she had invented and then promptly discarded after Juno and Venus mocked her. He played such beautiful music that he decided to challenge Apollo to a contest judged by the muses. After losing unfairly to the God, Apollo has Marsyas flayed.

So, why are these stories about the maybe siblings of Orpheus important? Well, one, they establish the sons of Oeagrus as musicians who have tragic stories often related to their music, and two, the lineage of Greek heroes is often important in understanding their fate. Which means Orpheus never had a chance.

Orpheus and the Argonauts

No matter which lineage Orpheus hailed from, it was his incredible music that would shape his fate. His music could make trees and rivers bend! This gift earned him a place on the Argo, alongside other heroes like Jason, Castor and Pollux, and Heracles. Atalanta is also sometimes part of the group but other times she is not.

In his most famous tale, the Argo was sailing past Sirens, bird-women that sang songs to lure sailors to their deaths. Orpheus stood on the bow and played his music to rival that of the Sirens, and everyone except for one hero ended up resisting the temptation of the siren song. Even that one hero was saved by Aphrodite and spirited away to safety. Orpheus’ role on the ship was one based on his musical prowess and as they traveled, he established many rites in various places.

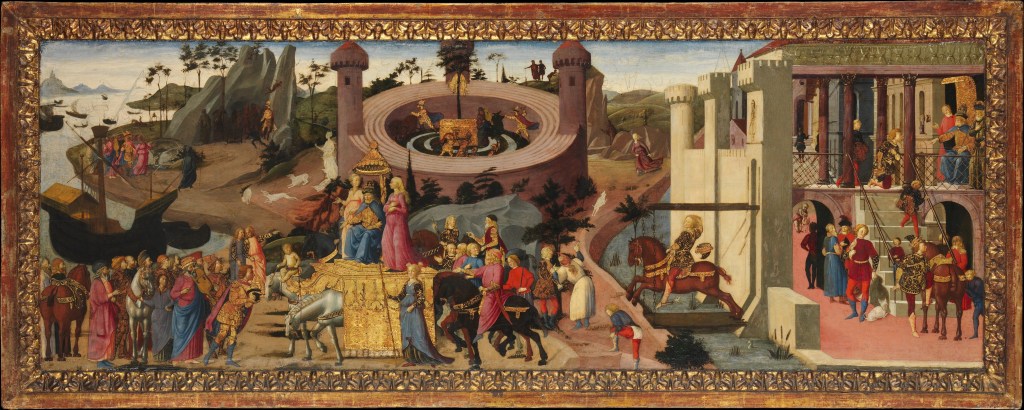

See if you can spot Orpheus in Jacopo di Arcangelo’s “Scenes from the Story of the Argonauts.”

Orpheus and Eurydice

After the Argonauts retrieved the golden fleece and disbanded, Orpheus returned to Thrace, where it is assumed he met Eurydice. During their wedding, many muses and deities arrived to celebrate and among them was Hymen, the god of the marriage hymn, sometimes considered a son of Apollo and a muse, either Calliope or one of the others (add him to the family tree).

His presence at a wedding was meant to bring good fortune, but what happened at Orpheus and Eurydice’s wedding was unusual. Hymen arrived, but he did not speak the usual words, look particularly joyous, or bring any good luck. To make matters worse, his torch sputtered, and the smoke was so thick that it created tear-provoking fumes and could not be lit properly.

Talk about a bad omen. Not long after the celebration, Eurydice was walking in a field when she was bitten by a serpent and died. That’s all we get from Ovid, but in Virgil’s version, events were slightly more sinister: she was chased by the god of beekeeping, Aristaeus. In trying to evade him, she was bitten by a snake and died.

Never had the gods heard such a sorrowful cry as when Orpheus found the body of his beloved wife. He filled the heavens with the moans of his grief and decided that, since he had nothing to lose, he would appeal to Persephone and Hades himself. Armed with his lyre, Orpheus journeyed down. His music granted him passage aboard the Styx with Charon and calmed Cerberus. Eventually, he made it past the throng of ghosts and reached an audience with Persephone and the Lord of the Shadows.

Striking his lyre, he began his sorrowful plea. He sang that he was not there to see Tartarus or bind Cerberus as others had. He had come to find his wife after trying for so long to accept her death. He had tried, but Love had won out, and he had come to plead his case.

In Ovid’s version, Orpheus alluded to not knowing if the God of Love was recognized in the Underworld, but if the story of Persephone’s abduction was true, then Persephone and Hades had also been wedded by Love. This may be a reference to myths placing the blame for Hades’ sudden desire for Persephone on an arrow shot by Eros as commanded by his mother, Venus. It could also simply mean that, as husband and wife, they surely understood love.

Orpheus continued to beg for Eurydice’s death to be reversed. He sang that they would eventually return to the underworld as all souls do, but he wished she could live a long life first. He asked for this gift, and if the Fates refused, he was determined to stay, leaving Hades to delight in both their deaths.

The Descent and Resurrection

As he sang, he brought the House of the Dead to its knees. The bloodless ghosts wept, and even Sisyphus sat idly on his rock as he listened. The Furies’ faces were wet with tears, and the King and Queen of the Underworld could not refuse Orpheus’ prayer. They called for Eurydice and granted her the gift of life, on the condition that Orpheus not turn his eyes behind him until he had emerged from the Vale of Avernus.

Orpheus and Eurydice by Peter Paul Rubens

So, Orpheus and Eurydice traveled upward, through still silence, steep and dark, until they neared the threshold of the upper world. Afraid she was no longer there and eager to see her, Orpheus turned his eyes. In an instant, all his efforts were wasted.

In Ovid’s version, Eurydice only cried a farewell, for what accusation could she cast on her husband’s fault? What could she complain of- his great love? In Virgil’s tale, Eurydice called her husband’s name and asked what madness had destroyed her and him. The Fates were calling her, and she was taken, wrapped in vast night. She cried her farewell, and then, like smoke vanishing in the shadows, she was gone.

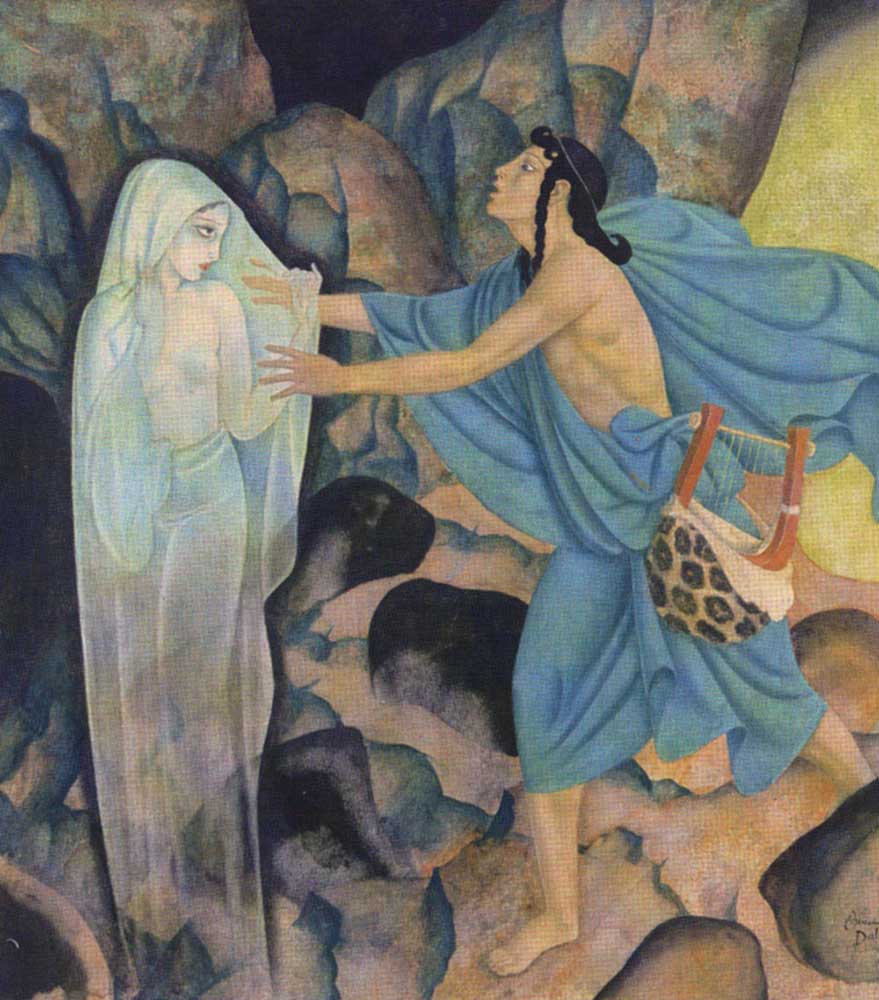

Orpheus and Eurydice by Edmund Dulac

The sight of his beloved’s senseless second death filled Orpheus with terror. He felt petrified, as if turned to stone, with the guilt of his wife’s death weighing on him. Orpheus tried again to cross the Styx, but the ferryman denied him passage. Even his hopes of death were ignored, and he sat on the banks of the Underworld for seven days, nourished only by grief and anxiety.

Orpheus Returns to Thrace

Finally, Orpheus wandered back to the upper world, but he never forgot his wife, his Eurydice. He ignored women altogether and sought friendship only among the men of Thrace. In one translation of Ovid’s book, Orpheus sings about various other myths, such as those of Ganymede and Pygmalion.

Time passed, and his refusal and rejection of women eventually led to his tragic demise. The Thracian women, followers of Dionysus, grew tired of being ignored. They threw sticks and stones at the singer, but even the weapons were charmed and refused to harm him. Enraged, they fell upon him and dismembered him in a frenzy—a not uncommon act for followers of Dionysus, known as sparagmos. This can be seen below in The Death of Orpheus by Nicolaes Knüpfer.

They tore his head from his body, and it floated down the river until it reached Lesbos, where Apollo saved it. Ovid writes that the ghost of Orpheus sank under the Earth and made the same journey he had before, until he reached his wife. Now, they walk side by side.

Some versions explain the women’s frenzy differently. In Hyginus’ Astronomica, Aphrodite sought to punish Calliope for her judgment on Adonis. (Adonis was a youth both Persephone and Aphrodite tried to claim, and Zeus let Calliope judge the outcome: each goddess would have him for half a year). In an act of revenge, Aphrodite stirred the women of Thrace with love to seek Calliope’s son, Orpheus, so they would tear him limb from limb.

Another version says that, in his grief and devotion to Apollo, Orpheus angered Dionysus and his followers by shunning the God. Either way, Orpheus’ connection with Dionysus is something to explore if you want to learn more about the Orphic myths. Especially the connection between Orpheus and Dionysus-Zagreus.

Image of Zagreus and Dionysus from Supergiant’s game Hades which is a phenomenal game. Hades 2 releases today so make sure you check it out if you love mythology and games!

The Oracle Orpheus

Now, there are variations when it comes to Orpheus’ fate after the dismemberment, and this is where the story gets really messy and muddy.

In some versions of the story, Orpheus’ head traveled down the river and ended up in Lesbos, but instead of being saved by Apollo, it was placed in a shrine. Now, the Athenian writer Philostratus wrote in the Life of Apollonius that Orpheus’ head would give prophecies in this shrine before Apollo told him to stop, since men no longer flocked to Delphi where Apollo’s oracles were. But other tales say that the head was buried in Lesbos and a shrine was erected where an oracle would give prophecies- not saying that Orpheus’ head was the oracle.

And with that, dear travelers, we also leave you with the age old question of why did Orpheus turn? Was it the same curiosity that is intrinsic to human nature, the very same one that made Icarus fly too high and Pandora open the jar? Was it love and the inability to cross the threshold into the living without guaranteeing Eurydice was with him? Or was it simply foolishness and forgetfulness- a habit to turn to check that cost him his wife.

Whatever your answer is, if you want to snag a piece of Orpheus for yourself, you can look up at the night sky, where Calliope carried Orpheus’ lyre after his death to form the constellation Lyra.