The famous legend of “Saint George and the Dragon” is as iconic to the English as Jack and the Beanstalk and a Christmas Carol. The original story was a lot more intense than the abridged version we all know. For our ‘Five Fantastic Finds’ you can hear about religious myths and canon, damsels in distress, the origins of slaying dragons, the etymology of George and the cost of hiring a hero.

If you haven’t listened to the story yet, be sure to listen here or download it wherever you listen to your podcasts! Let us know what you think in the comments or reviews.

Welcome back to Tales from the Enchanted Forest! Today, we are exploring a new type of hero! The saint and the dragon slayer himself- Saint George. If you’ve stepped foot in the United Kingdom then you’ve seen the five hundred pubs named after him so it’s time to explore his story!

However, despite how popular the story is for the English who refer to him as Sir. George, the actual origins of the story come from Greek and Georgian manuscripts. The earliest records are from the 5th century where the texts describe his martyrdom and his turmoil with King Dadianos or Diocletian. Towards the 12th century, we see the motifs of Saint George saving a pagan Princess and slaying a dragon. One of our sources comes from the 11th century with Historian E. Privalona and Kevin Tuite which looks at frescos, manuscripts and translations following the miracle narrative. We also used the more popular version of the story from the 12th Century, Golden Legend: Or, Lives of Saints by Jacobus de Voragine and translated by William Caxton. The story can also be loosely attributed to Epics like the Georgian romance, Amiran-Darejaniani, and Persian texts like the Shahnameh!

Careful Fox! A dragon quickly draws near,

He claims this podcast as we tremble in fear.

He kills all who approach and all who dare,

We might need more than our wits and a prayer.

But if we have faith and the will to fight,

Surely we can spare the young this night.

So gather travellers, Christian or pagan,

As we tell the tale of Saint George and the dragon.

Art by: Vladimir-Kireev

Part I – The Dragon Dilemma

A long time ago, there was a city in Libya named Silene. Near the City there was a shimmering lake, so big that one could mistake it for the sea. This was the source of fresh water for the City and surrounding farmland. But one day, a great dragon appeared and claimed the lake as its lair. Understandably, the citizens were not thrilled with this development.

The actual location of this is interesting because you can almost trace the story based on how and where the authors chose to place it. The earliest texts of the story take place in a city called Lasia, ruled by a King named Selinos. Some of the Greek texts also refer to the city as Lasia but with various spelling changes. It’s interesting that in the best-known version, the Jacobus de Voragine, the name of the city was called Silene and the location moved to Libya.

Fox

Immediately, the king mobilized all the soldiers and set out to slay the evil dragon. However, once they saw the dragon and heard its mighty roar, they grew frightened and ran away. Not that it did them much good, for that night, the dragon attacked the city with its venomous breath.

Image by Ksenia Kaverina

The people panicked, for they knew they could not fight the dragon and it would only be a matter of time before it destroyed the city. So they decided to offer two sheep to the dragon every day in order to satiate the creature. And for a time, this worked. But soon, the city ran out of sheep, but the dragon was still ever present. Gosh, it’s like nobody has had a pet before! If you keep feeding it, of course, it’s going to keep coming back for more food!

At this time, the king decreed that all young children and youth would be entered into the world’s worst lottery ever. Where the winner would then be offered as tribute to the dragon, and when they say all children, they mean all! No matter their status, whether they were the poorest of the poor or one of those snobby preppy noble kids, all would be entered into this game of chance.

This motif of sacrificing youth and then sheep actually is reminiscent of the Shahnameh where the demon-king Zahhak grew serpents on his shoulders that needed brains to survive. Two heroes chose to give him one human brain and one sheep brain for the daily sacrifice instead of two human brains every day. If you’re a bit nerdier like me then it’s also cool to note that the word used to describe the dragon here was the same word used for Zahhak’s demons in the translations of the Shahnameh. However, despite my current obsession with the Iranian Epic, there are worldwide stories of human sacrifices with some of the most predominant ones being in Grecian stories. We have our favourite, being the tributes to the Minotaur which included the Athenian Prince, Theseus.

Fox

And so weeks and months went by and the angry, anguished citizens became cold and numb to it all, as one by one, child after child, youth after youth, were delivered to the dragon. Eventually, the king’s own daughter was selected. The king was devastated and begged the people to spare his daughter. He offered all his gold, silver servants, his palace or anything they wanted if he could just keep his daughter. But his pleas fell on deaf ears as people had no mercy for the king that sent their own loved ones to the dragon already, so they flat-out refused his offer.

Defeated, the king accepted this fate but begged that he could have eight more days to say goodbye to her. For some reason, the people did agree to this. Whether they did have some mercy or maybe he bribed them for this, the text doesn’t say. Either way, after the eight days, the king dresses his daughter up like a bride before sending her off to the dragon.

Part II – A Hero Appears

Now it just so happens that at this time, a knight known as Saint George was passing through the area. See Georgie boy here had been released from his service under the Roman Emperor Diocletian, and he decided he should probably check in with his mom or something back in his hometown of Cappadocia, which today would be found in modern-day Turkey. So George is riding his horse, minding his own business when he sees a beautiful maiden weeping by a lake. Being the archetypal knight that he was, he rides up to her and asks what is wrong.

At first, she simply refuses to tell him anything, saying the story will take too long to tell and that he should leave quickly before it’s too late. But George refuses to leave a damsel in distress and insists she tells him what’s going on. Reluctantly, she tells the tale of her city and the dragon and how she must be sacrificed to save her people. She asks Saint George one last time to leave so that he may save himself, but he vows to protect her from this evil dragon.

So he sits by her and waits. But it’s not long until the huge dragon emerges from the lake. George took the initiative and charged at the dragon with his spear. Sinking the spear deep into the dragon’s side, he turns to the princess and asks that she toss him her belt.

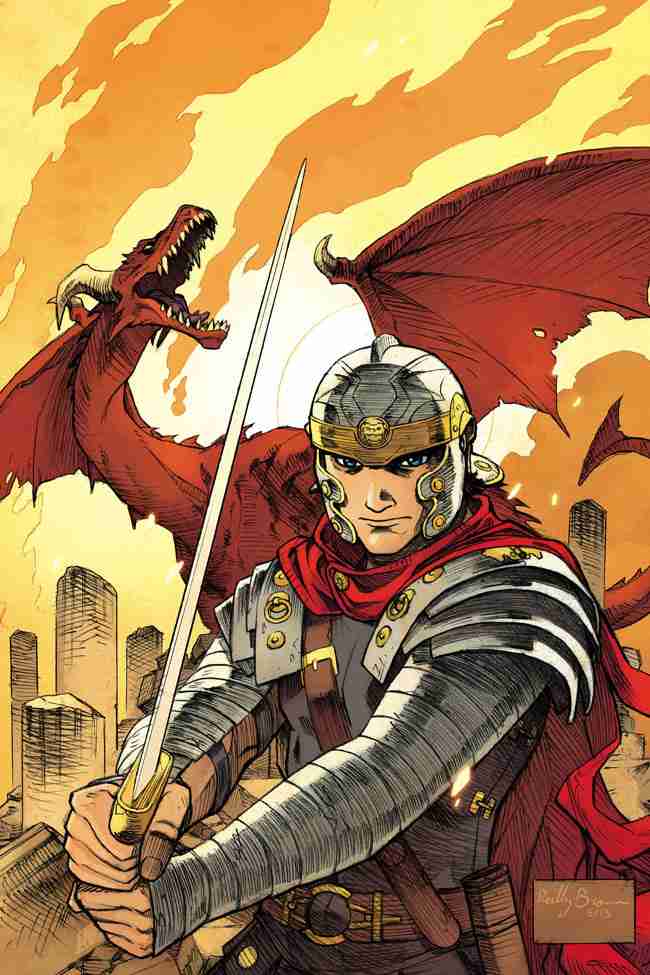

Art By Reilly Brown

Without question, she removed it and tossed it to him. Snatching the belt from the air, Saint George said a quick prayer before leaping onto the dragon’s back. He tied the belt around the dragon’s great neck and immediately the dragon became docile tugging at the belt, Saint George and the princess led the dragon back to the city.

The people were amazed and frightened of the dragon being in their city. Saint George told the people “Fear not, rather stand and see God’s deliverance”. He then called all the people to accept Jesus Christ as their lord and saviour, and once they had, only then would he slay the dragon. Because everyone knows that subtlety threatening people, is the best way to get them to join your religion.

The people quickly agreed to this and thousands of people were then baptized. The people rejoiced and thanked Saint George for freeing them from the evil dragon. Saint George’s story would continue, after all, he was still on his journey home, but that is where our story ends today.

Saints and Christian ‘Mythology’

Often we wonder why some tales on Gods are called “myths” and others are considered sacred religious texts. Where do we draw the line? In the general sense, myths are traditional stories and scholars often define myths as traditional stories that were believed as true and include a diverse cast including Gods, heroes, and monsters. These stories are important culturally and seek to explain a people’s history.

Over time, the idea of myth became seen as a fictional story and some religions rejected the term to refer to their own sacred stories. However, Christian writers and scholars have made some attempts to broach the idea of Christian mythology which refers to the non-biblical legends centred heavily around Christian motifs and themes. These stories are fantastical in the same sense as the Greek myths with heroes and monsters, in this case, the story of Saint George and the Dragon, but also King Arthur and his Knights, Parsival, and even the works of C.S Lewis who believed in the idea of ‘true myth.’

It is important to mention that while the genre of Christian mythology is closely associated with Christianity and Christian themes, this branch does NOT include biblical stories.

In all honestly, it’s hard to tell if these stories were intended to be religious or if they were religious based on the context of the times since any story written during a heavily religious period will have those themes. Even poor Saint George’s dragon story was held up for questioning in the 16th century by Pope Clement VII and others who allegedly decided it was offensive and had it removed from the official biography. No one is safe from de-canonization!

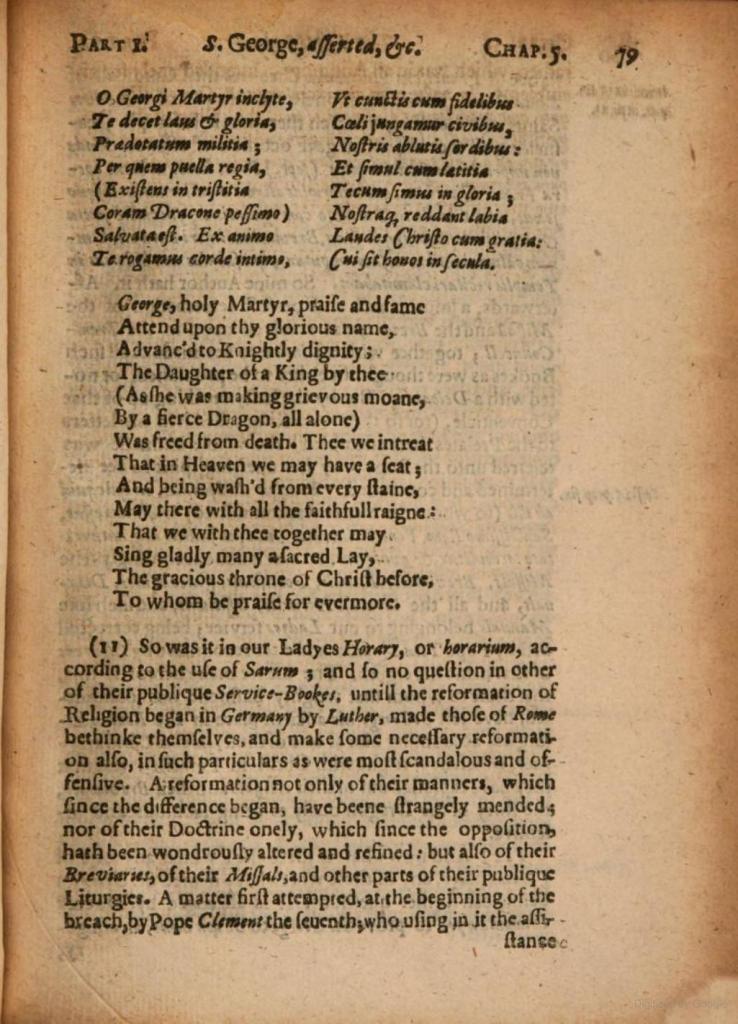

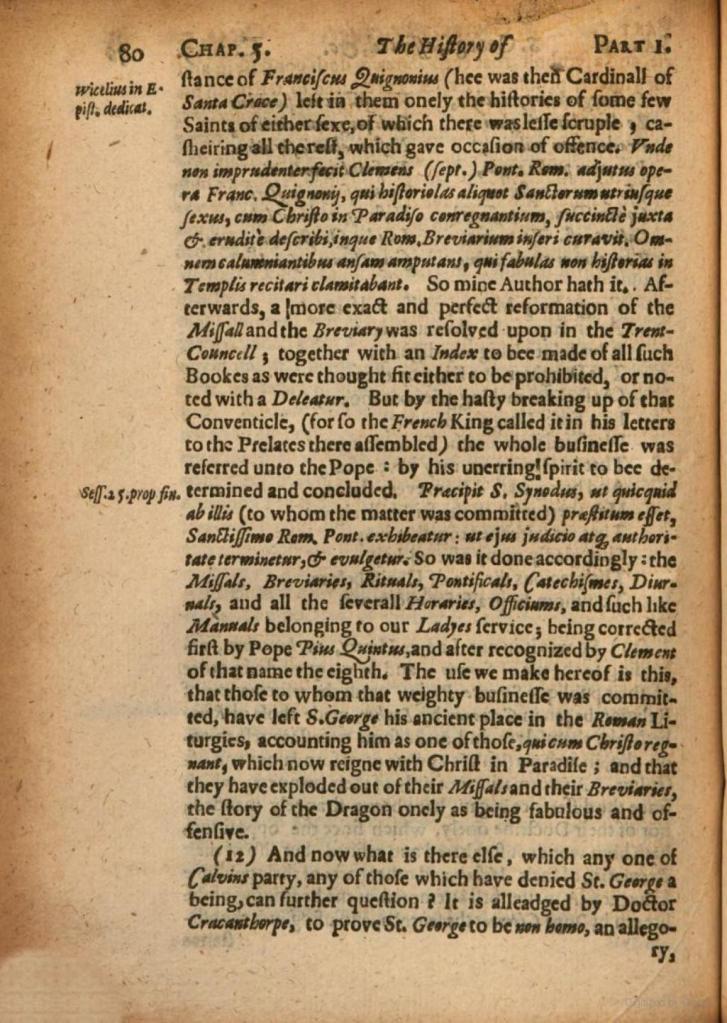

These allegations come from: The historie of that most famous saint and souldier of Christ Iesus ; St. George of Cappadocia (1633).

Transcribed as best as I could from the pages above and shortened for our needs: “[In reference to St. George and Dragon] So was it in our Ladyes [Horay, or horarium,] according to the life of Sarum ; and so no question in other of their publique Service-Bookes, until the reformation of Religion began in Germany by Luther, made those of Rome bethink themselves and make some necessary reformations also, in such particulars as were most scandalous and offensive. A reformation not only of their manners, which since the [difference] began, have been strangely mended, nor of their Doctrine onely, which since the opposition hath been wondrously altered and refined……A matter first attempted at the beginning of the breach by Pope Clement the seventh; who using in it the [assistance] of [Francisco de Quiñones] (he was then Cardinal of Santa Croce) left in them only the histories of some few Saints of either sexe, of which there was less scruple, [casheiring*] all the rest, which gave occasion of offence…The use we make hereof is this, that those to whom that weighty business was committed, have left S. George his ancient place in the Roman Litugies, accounting him as one of those, [quicum Christoregnant] which now reigne with Christ in Paradise; and that they have exploded out of their Missals and their Breviaries, the story of the Dragon onely as being fabulous and offensive….” pages 79 and 80.

Damsel in Distress Trope

When I think of fairy tales, the first thing I think of is a knight in shining armour rescuing a princess. Very much like what happened in today’s tale in Saint George and the Dragon. There is something about a hero overcoming impossible odds to rescue the damsel in distress, that just seems to resonate with me. But I have noticed a trend over the past couple of years that seems to spit on this trope as our society has empowered women and there is a distinct value in our culture to be self-sufficient. While I’m all for both of these things, the reality is I feel we are overlooking what makes this trope really work.

Sure, in the classics, the damsel is often no more than a prize to be won and could easily be replaced with a lamp for all her character adds to the story. This is likely what people are thinking when they spit on this trope. So to subvert this trope people went “hey, what if we gave our damsel a personality??”. Shocking I know but sadly authors tend to have interesting characters that suddenly lose all their unique traits the moment they get kidnapped. This is often a result of the creator wanting to focus on the hero. But it’s such a missed opportunity for exploring how the damsel character would truly cope when they have been taken captive.

In the best-case scenario, the damsel will make active attempts to escape their capture or to gain intel on their enemies. Even if their attempts fail, we get to see their wits and resourcefulness and can maybe even surprise their captors.

One good example of this is lieutenant Rita Hawkeye from Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood. From the start of the series, Lieutenant Hawkeye is consistently shown to be the most competent and elite fighter across the board. And no matter how tough the situation is, she is nearly always composed and able to keep the bigger picture in mind, and that attitude stays with her, even when she is unknowingly damsel.

While she is never physically restrained like a traditional damsel in distress, she is still very much taken hostage to keep Colonel Roy Mustang in check. After being transferred away from her Mustangs team, her keen instincts quickly clue her into the situation and the metaphorical knife to her neck from her new superior. If she was a traditional damsel in distress, this is when the distress ball comes in and loses her personality. But instead, she keeps a level head and even confronts one of her captors, about his secret dual identity. Even while captured and unable to escape by herself, we get some really great solid character exploration from both Lieutenant Hawkeye, as she continues pushing forward even while damsel. And Colonel Mustang who, for the first time in the series, was forced to cope without his right-hand woman.

What makes this trope work so well is that no matter how self-sufficient a character is, they will always need help at one point or another. And that’s true for all of us. It’s a great reminder that we all need help sometimes. The trope can show off how much a character means to the others and that the hero can and will come to their aid. We get a fun rescue and see how our heroes cope without the damsel character in the group and vice versa.

Slaying Dragons

Dragon slayers are a huge fantasy trope nowadays, but where did the stories start? Let’s head all the way back to some of the first dragons, Mesopotamia’s Mušḫuššu, the Nordic Fafnir, and the countless unnamed dragons depicted in art from all over the world.

Some cultures saw dragons as Gods, nature deities or monsters, but the idea of dragon slayers doesn’t appear in solidified form in the western world until the Norse Hero Sigurd!

While the stories of Fafnir and Sigurd don’t appear till later, there is a Swedish carving called the Ramsund Carving from around 1030 AD that shows an account of Sigurd’s deeds- one of which shows him slicing through a large serpentine creature. Following Sigurd is the figure of Beowulf, who was mortally injured by a dragon after a battle.

Art of Beowulf and the dragon by Armin Rangani

In Greek mythology, we also have Cadmus, the dragon-slayer, as well as Apollo’s defeat of Python, and we can’t forget our Shahnameh heroes.

This dragon-slaying trope goes hand in hand with dragon-taming tropes where the heroes work with the dragons instead of conquering them. These stories are more common in Asia, where dragons and the Naga were sometimes seen as neutral Gods or creatures.

Modern media likes to play with this trope and combine the two as we see in shows like Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon, as well as other series like Christopher Paloni’s Inheritance Cycle, Avatar the last Airbender, How to train your dragon, and the Dragon Prince.

Name a better love-hate relationship over time than monsters and monster hunters! Looking at you, Shrek.

The Etymology of George

In the western world, George is a pretty common name. In fact, in the past couple of years, George has been the fourth most popular baby boy name in Britain (according to BabyCenter). And it has been growing in popularity as a girl’s name in America. But what is in a name? For a George by any other name would smell…of something I am sure.

The name George derives from the Greek Georgios and it means “farmer” or “earth-worker”. And while this name has existed for a long time, it only started becoming popular once the Christian Church deemed Saint George, as a, well Saint. That’s right, it’s thanks to today’s story that there are so many people named George today! So that’s George Lucas, George Clooney, all the King George’s, George Orwell, George R.R Martin, George Weasley, George Costanza, the list goes on and on and on.

The point is, if you or someone you know is named George, you can probably thank Saint George and his dragon-slaying antics for that.

A Princely Ransom

So, usually, when we think of ‘heroes’ we think of people who just do good for the sake of good. They save the Princess, fight the monsters, restore good, banish evil, and all for the simple price of /praise and honour! Maybe even notoriety. It’s like when social media influencers go on reality shows to gain more followers or popularity. This topic gets brought up a lot when discussing superheroes and how they can afford to be crime fighters if they don’t already have private wealth. Sure, Stark and Batman can afford to damage their suits and pay their medical bills but what about a hero like Spiderman?

Some of us have bills to pay. So, what about the legendary heroes who are ‘work-for-hire’ or demand payment in exchange for their adventures? And we aren’t talking about the trope where you save the King and he gives you bags of gold and his daughter’s hand as a prize afterwards. We’re talking about naming your price! George is our first obvious example since he demands the conversion take place or he will release the dragon again. On a larger scale, even the Gods get angry when they aren’t paid for their dues.

An example of the “Show me the Money” Trope going wrong can be seen in the origins of the Trojan war with King Laomedon stiffing not just the hero, Heracles but also two Greek Gods. Apollo and Poseidon had built the great walls of Troy but were not paid by Laomedon who found some or the other excuse to avoid paying. So, Apollo sent a plague into the city and Poseidon sent storms and waves to destroy it. Seeking an oracle instead of paying his bills, Laomedon was told that he would be saved if he sacrificed his daughter, Hesione, to a sea monster.

Heracles and his crew were passing by and Heracles offered to save the girl if only Laomedon would exchange her safety for his prized horses from Zeus. Of course, after saving the girl, Heracles was also stiffed by the King and so he ravaged Troy. Leaving only the young Prince Priam alive at his sister’s behest. I’m sure had the city refused to convert, George would not have had any hesitations also creating chaos.

Italian School from The Fitzwilliam Museum